By Marcus R. Lee

In the ever-evolving hospitality industry, the question of how to effectively compensate hotel operators remains crucial. While the basic premise of paying managers for their management skills holds true, the prevalent incentive fee structures may no longer adequately align with market realities, particularly for owners.

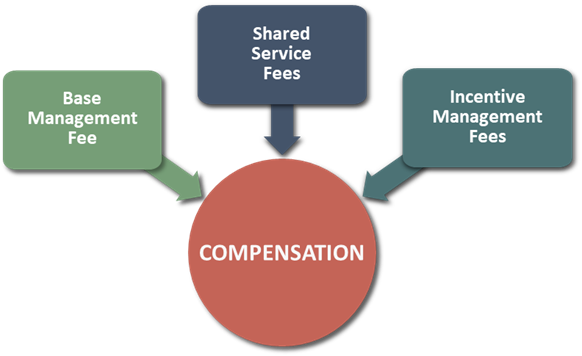

Management Fees Breakdown

Hotel management companies earn fees through three main avenues:

In the typical hotel management agreement, hotel management companies are typically paid a base fee equal to 2.0% to 4.0% of total operating revenue—3.0% being the most common—plus an incentive, typically an incentive management fee (IMF). The base management fee typically covers the services provided by the management company for the day-to-day operation of the hotel, including overall management oversight, staffing, training, budgeting, financial reporting, and operational support. This fee is intended to compensate the management company for its expertise, time, and resources expended in managing the property and ensuring its operational success, although it does not directly tie the management company’s earnings to the hotel’s profitability like an incentive management fee does.

Shared services fees in hotel management agreements refer to charges levied on a hotel for the centralized services provided by the hotel’s management company or parent brand, such as marketing, reservations systems, and technology support. These fees allow for economies of scale by spreading the costs of these services across multiple properties within the management company’s portfolio, potentially leading to enhanced operational efficiency and improved profitability for individual hotels by reducing their direct costs for such services. Shared services fees typically differ from operator to operator given the variability of corporate employee salaries and the portfolio size of each management company. Shared services fees are often standardized across a hotel operator’s or brand’s portfolio, reflecting the costs of centralized services that benefit all properties. This standardization means there is little room for customization or concessions on a per-property basis, as operators are keen to maintain consistency and fairness among all their managed hotels.

Incentive management fees are a compensation mechanism designed to align the interests of the hotel manager with those of property owners. These fees are typically structured on top of a base management fee and are calculated based on the hotel’s financial performance exceeding certain predefined thresholds. Incentive fee structures vary, but over the last decade or so, they have coalesced around a formula that pays managers between 10% and 20% of cash flows that exceed a certain performance threshold. This threshold is generally reached when the adjusted gross operating profit (AGOP) exceeds a return on the owner’s investment (often the development cost associated with the project) of between 8% and 12%. AGOP is typically defined as the gross operating profit (GOP) less the following exclusions:

The idea behind the IMF is to incentivize operators to surpass financial benchmarks for the GOP and thereby earn additional fees, which theoretically encourages them to operate the hotel more efficiently and effectively, leading to mutual benefits for both the management company and the hotel owner. However, increasingly, owners are experiencing financial pressures from all angles due to the rising costs of goods, labor, insurance, utilities, and everything in between, prompting a rethink of all expenses, including management fees.

Incentivizing managers based on the AGOP is meant to align the interests of management companies with those of owners. This practice, however, does not adequately compensate for an important facet of management—the manager’s performance. The current structure of incentive fee thresholds is affected too much by the general performance of the market, rather than operating results achieved by management exclusive of market performance.

As a case in point, when the lodging market was in the doldrums due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, management companies struggled to earn the incentive management fee; however, when the lodging market recovered in 2022 and 2023, management companies began earning record-breaking incentive management fees, lifted by strong topline revenues across the board as travelers engaged heavily in “revenge travel.” Notably, Marriott International, the world’s largest hotel operator, announced that in calendar-year 2023, it earned 20% more incentive management fees than in 2019, its prior peak.[1] Similarly, Hyatt Hotel Corporation announced that in Q3 2023, 23% more Hyatt-managed hotels activated the incentive management fee clause than in the same quarter in 2019, prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.[2]

A better incentive management fee system would compensate high-performing managers for better-than-average performance in both good and bad years based on a variety of metrics, not just a percentage of AGOP. This incentive methodology would be similar to the bonus structure of a hotel general manager.

An Alternative Incentive Fee Structure

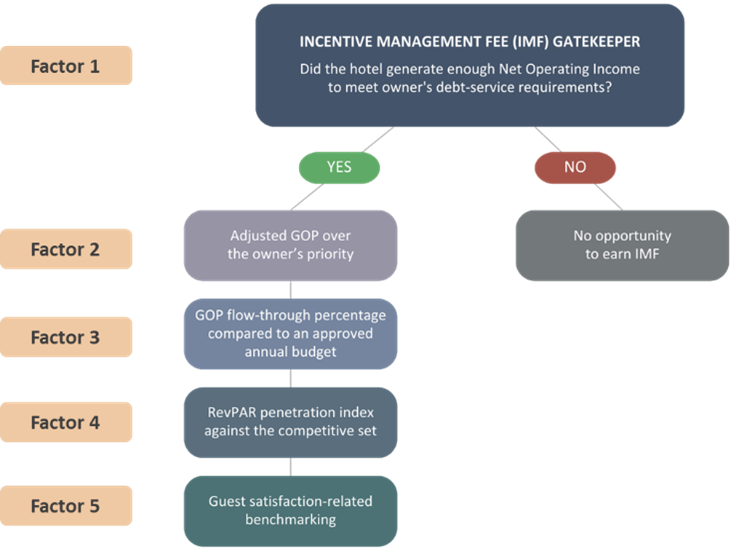

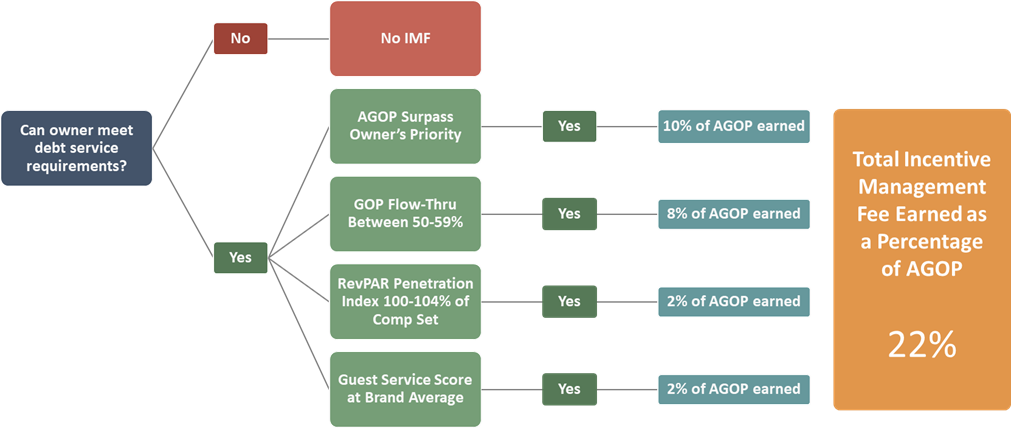

Conceptually, a management company’s effectiveness is evidenced by two main results: the ability to generate an appropriate share of top-line revenue within the relevant competitive market (maximizing RevPAR penetration[3]) and the ability to convert that revenue into as much sustainable cash flow available to the owner (GOP) as possible. Thus, a more comprehensive way to calculate the incentive management fee payout would include considerations of the following five factors:

The first consideration (factor #1) should be a gatekeeper for the operator’s ability to earn the IMF. The flat percentage incentive fee tied to the AGOP exceeding an owner’s priority (factor #2) would form a portion of the total IMF but at a lower weight. The final three factors would then comprise the remainder of the incentive management fee formula, carrying different weights as negotiated between the operator and the owner/owner’s representative.

Owner Debt-Service Threshold

The first threshold a hotel operator should be expected to clear in order to earn an incentive management fee is the hotel generating enough return for ownership to meet its basic investment parameters, such as debt-service requirements. Hotel operators have traditionally explained the current structure of incentive fees as a way of sharing risk with owners. However, risk implies potential losses, which management companies distinctly do not share based on the current fee structure. Therefore, if a potential operator cannot or does not expect to achieve results strong enough to meet the owner’s debt service, then either a separate negotiation between the operator and owner should occur, or the operator should reconsider accepting the management contract.

Additionally, there are many scenarios where operators earn an incentive management fee by surpassing the owner’s priority threshold, but the owner is left with insufficient net operating income (NOI) to cover the debt service on the property. If a hotel operator’s ability to earn an incentive management fee were placed subordinate to the owner’s need to service debt on the property, hotel operators would be highly incentivized to be both exceptional in revenue earning and prudent in expense management to ensure these revenues are carried over to the bottom line. If an operator does not deliver a high enough NOI in any given year, barring certain exceptions, no incentive management fee should be paid out for that year.

Adjusted Gross Operating Profit Over Owner’s Priority

As is currently set out in most existing hotel management agreements, the management company is usually awarded the IMF in a given year if the AGOP exceeds the owner’s priority amount. The owner’s priority amount is typically a hurdle level equal to between 8% and 12% of the owner’s investment into the project or development costs. For example, if an owner spent $10 million developing a hotel, the owner’s priority amount might be $1,000,000 (10% of total development costs); in this scenario, if the hotel’s AGOP for the year exceeds $1,000,000, then an IMF would be paid out to the management company.

This practice sets the correlation between the owner’s investment in the project and an operator’s performance-based bonus, aligning the management company’s interest with that of ownership; however, this alone is inadequate for incentivizing a management company’s performance. Adding other management performance metrics in addition to measuring AGOP over the owner’s priority would allow owners to reward truly exceptional managers focused on multiple aspects of the hotel’s operation.

Limiting the management company’s IMF earnings from this criterion would allow for a more balanced total IMF payout. For example, lowering the amount the management company can earn from fulfilling this benchmark from the current 15–20% of AGOP to just 10% of AGOP would leave space for management to make up the difference via other criteria.

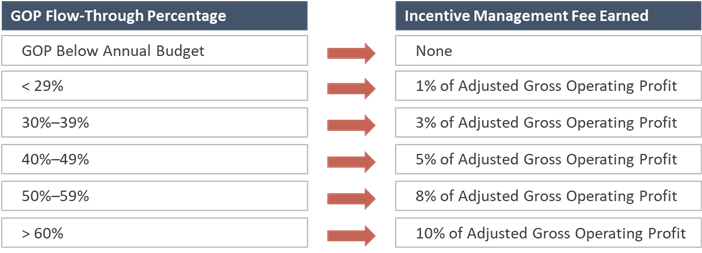

Gross Operating Profit (GOP) Flow-Through

GOP flow-through is a critical measure used to evaluate a hotel’s operational efficiency and profitability. It quantifies the percentage of incremental revenue that converts into GOP, essentially showing how well an operator manages the hotel’s operational costs and maximizes profit from increased topline revenue. Flow-through is derived by comparing the change in GOP against the change in total revenue over a specific period, offering insights into how effectively the hotel manager controls costs and generates profit from new revenue. A high GOP flow-through indicates strong cost management and operational efficiency, as a significant portion of every additional dollar earned contributes directly to the hotel’s bottom line. This is therefore a vital indicator for assessing an operator’s managerial effectiveness. As the IMF should essentially be a hotel management company’s reward for exceeding expectations, tying a portion of the IMF to the GOP flow-through is only logical.

Expectations are set each year through the annual budget. Every year, hotel management companies are expected to present an annual budget to ownership, establishing a transparent and accountable financial roadmap for the hotel. A budget outlines expected revenues and expenditures, as well as strategic initiatives for the year ahead, and is typically a collaborative process between the operator, asset manager, and owner. Annual budgets enable owners to assess the operator’s financial strategies, set performance benchmarks, and make informed decisions to ensure the property’s success and profitability. Adhering as closely as possible to an approved financial budget is critical to balancing short-term operational needs with ownership’s long-term strategic goals.

The following table presents our recommendations for how operators should be rewarded based on various GOP flow-through targets. If a hotel does not hit the budgeted GOP, the management company should not earn the IMF attributed to this benchmark.

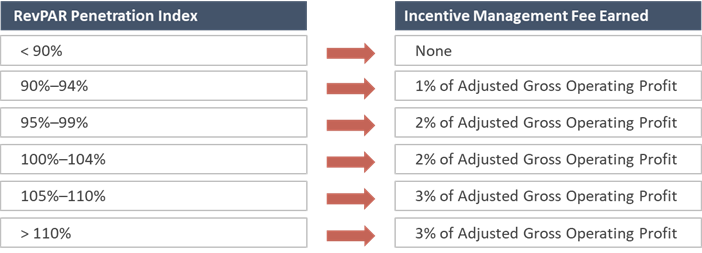

RevPAR Penetration Index

RevPAR penetration index is a performance metric comparing a hotel’s RevPAR against a selected competitive set. This index provides a hotel with a relative measure of its market performance by indicating how well it is capturing its fair share of revenue vis-à-vis its direct competitors. An index over 100% would indicate that the hotel is capturing more than its fair share of market revenue, demonstrating management achievement. Using the RevPAR penetration index as a benchmark for the IMF payout would incentivize hotel operators to constantly seek innovative ways to outperform its direct competitors. An incentive structure should then be set up that handsomely rewards managers who achieve or surpass the appropriate RevPAR penetration index benchmarks. A suggested structure is presented in the following table.

It is important to note that many management contracts include some level of recognition of RevPAR penetration in their performance clauses. Such clauses commonly suggest that if RevPAR penetration falls below a certain reasonably acceptable level (typically 85% or 90%) over a sustained time period (often over two consecutive years), there may be cause for termination. However, these clauses have typically been used only to guard against poor management performance, not to set compensation. Furthermore, the RevPAR penetration threshold level is usually arbitrary, without consideration of the subject property’s competitiveness relative to its competitors, since the competitive set is not usually finalized until a later stage.

Guest Service Score Benchmark

In the U.S., 72% of hotels are affiliated with a major hotel brand.[4] One of the benefits of a nationally recognized brand affiliation is the ability to benchmark, among other things, guest service scores against other similarly branded hotels. Marriott, for example, benchmarks its hotels across the following categories: Intent to Recommend, Elite Appreciation, Staff Service, Cleanliness, Food & Beverage, and Maintenance & Upkeep, among other categories. Hotels are scored out of 100 points for each category and ranked within their respective brands.

Guest satisfaction scores are correlated to profitability. High satisfaction scores often lead to repeat business and loyal customers, as satisfied guests are more likely to return to the hotel for future stays at a much lower acquisition cost to the hotel (compared to attracting a new guest). Additionally, in the era of digital platforms and social media, positive guest reviews and ratings can significantly influence the booking decisions of potential guests, increasing guest acquisition via a lower-cost method than, for example, digital marketing ads. As such, we recommend that a positive guest satisfaction score as determined by the brand—often at brand-average benchmarks—should be considered a success and rewarded through the incentive management fee. Non-branded hotels could be benchmarked via Revinate or another similar guest satisfaction tracking system.

The Holistic Scorecard

The table below shows the basic framework of a hypothetical incentive management fee based on the above scoring criteria and metrics. Naturally, the respective level of achievement and associated IMF that could be earned from meeting each criterion will have to be negotiated between the management companies and owners; the table below is an example for illustrative purposes, and deviation would be expected.

It is important to note that, however the IMF calculation is set up between the management company and ownership or the asset manager, an exceptionally performing operator should be more incentivized under this blend of criteria than they would be by earning the IMF purely based on the AGOP over owner’s priority threshold. This is the only way to win management companies’ buy-in to this innovative new model.

Conclusion

As referenced earlier in this article, owners are beginning to question the existing IMF system with sentiments such as, “Why should I pay an incentive fee if I can’t pay my mortgage?” While both operators and owners stand to gain from adopting the management fee structure proposed in this article, hurdles are anticipated before it gains widespread acceptance. As with any change, inertia will initially favor the status quo. Since the present system demands less accountability of management companies, there is likely to be some natural resistance to incorporate the proposed structure into their own management agreements. This is unlikely to change unless competitive forces compel management companies to eventually do so.

Thus, a targeted approach is needed to enhance an owner’s bargaining power in a management agreement negotiation. Historically, owners have engaged hotel consulting firms such as HVS for brand and operator searches and selections to create a competitive environment for both brands and management companies. The increased scrutiny and competition created by the request for qualifications (RFQ) process forces a brand and/or a management company to provide its best financial and contractual offer and gives owners a stronger position in negotiations. Strengthening an owner’s negotiation stance could potentially hasten the acceptance of innovative fee structures, such as the one presented in this article, paving the way for a more accountable and competitive hotel management compensation system.

[1] Excerpt from Marriott’s 2023 Q4 earnings call (transcript courtesy of www.seekingalpha.com): “Fourth-quarter total gross fee revenues grew 10% to 1.24 billion reflecting higher RevPAR, room additions, and strong growth in our co-brand credit card fees. Incentive management fees or IMF rose 17%, reaching 218 million driven by another quarter of significant increases in Asia Pacific. For the full year, gross fees rose 18% with record IMFs that were nearly 20% higher than our prior peak in 2019. Owned lease and other revenue net of direct expenses reached 151 million in the quarter and included substantially higher termination fees, primarily due to 63 million associated with the termination of a development project.”

[2] Excerpt from Marriott’s 2023 Q4 earnings call (transcript courtesy of www.seekingalpha.com): “Fourth-quarter total gross fee revenues grew 10% to 1.24 billion reflecting higher RevPAR, room additions, and strong growth in our co-brand credit card fees. Incentive management fees or IMF rose 17%, reaching 218 million driven by another quarter of significant increases in Asia Pacific. For the full year, gross fees rose 18% with record IMFs that were nearly 20% higher than our prior peak in 2019. Owned lease and other revenue net of direct expenses reached 151 million in the quarter and included substantially higher termination fees, primarily due to 63 million associated with the termination of a development project.”

[3] “RevPAR penetration” measures a hotel’s RevPAR (revenue per available room) relative to the RevPARs of its competitors. A hotel’s RevPAR penetration is calculated by dividing its RevPAR by the combined RevPAR of its competitors and is expressed as a percentage.

[4]Freitag, Jan. CoStar, “For Hotels the Future Is Branded. Or Is It?” March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2024.