By Dayk Balyozyan , Sophie Perret , Chris Martin

While hotel lease contracts have traditionally been very popular in Europe and continue to be preferred or required by many institutional investors, management contracts have become increasingly prevalent as many other investors have sought to share further in their hotel’s trading profit and, at the same time, most major international hotel operators have become far less willing to offer leases. A hotel management contract is defined as an agreement between a management company (or an operator), and a property owner, whereby the operator assumes responsibility for managing the property by providing direction, supervision, and expertise through established methods and procedures. The operator runs the hotel, on behalf of the owner, for a fee, according to specified terms negotiated with the owner. Negotiating the terms of a hotel management contract should not be approached lightly, as it can characterise the property’s identity for decades and produce differing results for owners. A well-negotiated management agreement should align the interests of both parties. As an owner, the major goals should be to select the management company that will maximise profitability and therefore the value of the asset, and to secure the best possible contract terms with that operator, while at the same time ensuring the operator is properly incentivised to maximise profitability. As a result of a gradual shift in hotel investment trends over the past 30 years, owners have generally developed a much greater understanding of hotel operations, and have become more sophisticated in their selection of operators and in the negotiation of contract terms, often with the help of specialist advisory firms. It has become increasingly common in recent years for institutional and financial investors and private equity funds to invest in hotel assets. Such investors typically aim to separate ownership of the physical hotel asset from operation of the business. In addition, the investment interest and associated increase in the amount of capital available for hotel investment from this wider pool of investors has further contributed to the increased sophistication of hotel investors, who often have in-house hotel asset managers or engage speciality consultancies or asset management companies to help monitor and drive peak performance from the operator. The most common of the management contract terms are listed below and described further in the following sections.

- Term

- Operating fees

- Operator performance test

- Approval rights

- FF&E and capital expenditure

- Territorial restrictions

- Non-disturbance agreements

- Operator guarantees

- Operator key money

- Termination rights

Please also refer to the comprehensive ‘HVS Hotel Management Contract Survey’ article written by Manav Thadani, MRICS, and Juie Mobar, based on a sample of 76 management contracts in Europe totalling 19,200 rooms. This survey is available in the HVS Bookstore.

1. Term

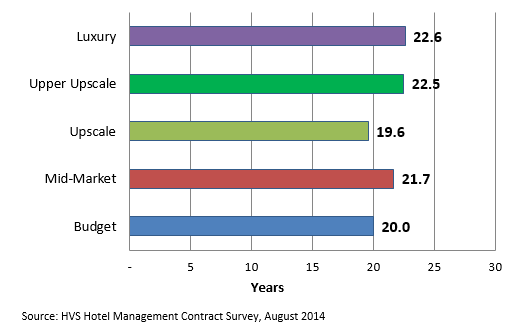

The term of a management contract is the duration the agreement is to remain in effect, generally calculated from the opening/effective date until the expiration of a specified number of years. Initial terms typically last between 15 and 25 years, depending on the brand and the positioning of the hotel as well as on the negotiating power between the owner and the operator. More upscale operators, such as Four Seasons and Ritz-Carlton, may require longer initial contract terms, often ranging from 30 years up to 50 years, or even sometimes longer. As a general rule, the higher the market positioning of the hotel, the longer the initial term. In Europe, the average length of the initial term is 21 years[1]; the average initial term length has shortened in recent years. The following table shows the average length of the initial term for hotel management contracts in Europe by market positioning, according to the HVS Hotel Management Contract Survey.

Figure 1: Length of the Initial Term by Market Positioning

Renewal terms are usually based on either the operator having further extension rights, or upon the mutual consent of the owner and the operator. Renewal terms tend to occur in multiples of either five or ten years. Most contracts offer two extension terms (sometimes more) on the condition that six months’ written notice is given prior to the end of the current term. For commercial reasons, brand operators prefer longer contract terms with renewal options in their favour, whereas flexibility is likely to be more important for owners and thus there is a preference for a shorter initial term and renewal options ideally only by mutual consent. There has been a noticeable decrease in the average length of initial terms across Europe, which can be attributed to the following factors:

- The proliferation of private equity vehicles in the hotel investment market in recent years has placed pressure on operators to offer more competitive, shorter initial terms, although these are generally coupled with more renewal options;

- The increasing competition amongst hotel operators seeking to broaden their distribution network;

- An increase in hotel investment in emerging markets along with the associated risks in such markets have led both operators and owners to negotiate contracts with shorter terms, to provide the opportunity to exit in the event of disappointing market conditions.

2. Operating Fees

Operators are remunerated with fees for the performance of their duties detailed in the contract. These management fees should be structured in such a way that they encourage the operator to maximise the financial performance of the hotel. Fees can be calculated by reference to various formulae. Typically, the operator’s fee will be split as follows:

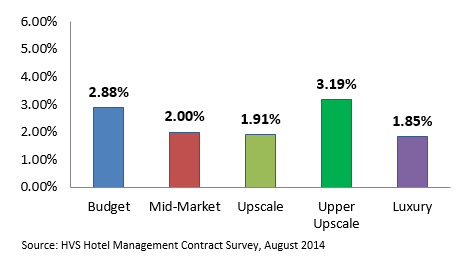

- A base fee, generally calculated as a percentage of gross operating revenue (ranging typically from 2% to 4%). While many owners would argue that an operator should ideally only receive fees based on the profit, not revenue, that the hotel generates, operators have successfully argued that they need to be protected with a certain amount of virtually ‘guaranteed’ income in order for them to be able to subsidise the costs of operating their organisations even during a severe market downturn when hotels’ operating profits may be significantly reduced or even, in the worst cases, non-existent for a period of time. There is evidence of the base management fee decreasing with a higher market positioning, as highlighted in the table below:

Figure 2: Base Management Fee By Market Positioning

- An incentive fee based on a percentage of the hotel’s operating profit. While the base fee encourages the operator to focus on the top line, the incentive fee ensures that there is also an incentive to control operating costs. Incentive fee structures have a wide variety of forms in practice. These incentive fees are generally based on a percentage of either the gross operating profit (GOP) before the deduction of base management fee or, more usually, the adjusted GOP (AGOP), calculated by deducting the base fee from the GOP. The incentive fee can be structured differently, with examples including:

- A flat fee structure, where the incentive fee is calculated as a percentage of GOP/AGOP. This percentage may be constant or scaled upwards throughout the term of the contract (usually by way of a ‘build-up’ in the first few years until the hotel’s expected year of stabilisation).

- A scaled fee based on the level of the GOP or AGOP margin that is achieved. This fee structure certainly rewards the operator for a more efficient performance and is becoming increasingly common.

- A fee linked to the available cash flow after an Owner’s priority return. The Owner’s priority return can be a fixed amount or a percentage of the initial (and sometimes future) capital investment. The operator will not receive its incentive fee until the owner’s priority return has been achieved for that year. This incentive fee structure is usually accompanied by provisions whereby the operator’s incentive fee is not ‘lost’, but only ‘deferred’, and then recouped in later years if and when the Owner’s Priority is exceeded by a sufficient amount to cover that year’s incentive fee as well as some or all of those incentive fees deferred from previous years. As deferred fees can create complications during the sale of a hotel (with purchasers often seeking a price reduction so they can cover this potential future liability that would ‘transfer’ to them), these types of incentive fee structures are becoming less popular with owners.

- Other fees and charges can be claimed by the operator, and are related to items such as centralised reservations, sales and marketing, loyalty programmes, training fees, purchasing costs, accounting or other costs. These fees are often defined as a percentage – between 1% and 4% – of total revenue or rooms revenue (as applicable, and varying between different operators).

There is a rising trend observed in the industry where operators are accepting lower base fees in return for higher incentive fees of up to 15% of GOP, which are designed to more closely align the operator’s interests with that of the owner – to maximise the operating profit of the hotel, regardless of the revenue. While a fixed incentive fee percentage ranging from 8% to 10% of AGOP was typical, it is becoming increasingly common to have scaled incentive fees. The tendency towards higher or scaled incentive fees versus higher base fees, rewards effective operators but also provides some protection for the owner’s cash flow/return in the event of poor operator performance or a market downturn.

3. Operator Performance Test

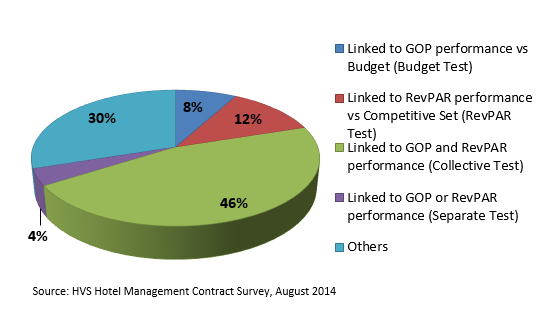

Performance tests allow an owner to terminate the management agreement should the operator fail to meet the agreed performance criteria after a period of build-up (test periods commence in the fourth year on average). Two types of performance tests are typically used, often jointly:

- Room revenue per available room (RevPAR) as a percentage of a mutually agreed upon competitive set (in Europe, the test is generally set somewhere between 80% and 95% of the weighted average RevPAR of the competitive set);

- The GOP level for an operating year should not be less than the mutually agreed budgeted GOP level (usually starts at 80%, up to 90% of the budgeted GOP, depending on the negotiation strength of both parties).

As highlighted in the following graph, these two performance tests are often used jointly in European management contracts.

Figure 3: Type of Performance Tests

A performance test usually starts from year thee or year four, after stabilisation of the new hotel, generally known as the commencement year. The performance test is usually deemed to be failed if both the RevPAR and the GOP tests have been failed for two years in a row. However, some unscrupulous operators have been known to sometimes artificially inflate RevPAR performance to meet the required standards, so the RevPAR test is not held as a reliable measurement tool by experts. It can also be challenging to agree the right competitive set and sometimes to find reliable RevPAR data for the competitive set. Furthermore, in case of a force majeure event or any peculiar event that is beyond the operator’s scope, then the performance test would not be applicable and the right of termination of the owner is not exercisable. Good performance tests are the ones that are enforceable, sensible and that truly reflect the relative position of the hotel. Major operators usually negotiate a clause with a ‘right to cure’ in the event of a failed performance test, allowing the operator to make a compensation payment to the owner. The typical right to cure usually includes a specific/limited number of times that the operator has the right to cure during the term of the agreement. We have seen recent management contracts which include performance tests based on TripAdvisor ratings and commentaries. However, these ratings are potentially influenceable by non-guests or biased by messaging bots. Other non-financial performance tests include the ones based on the number of materialised reservations generated through the operator’s distribution systems versus those that are generated by online travel agencies (OTA) or third parties. For more information on management fee structures and performance clauses, please refer to the HVS San Francisco article ‘Hotel Management Fees Miss the Mark’ by Miguel Rivera, September 2011.

4. Approval Rights

Approval rights define the extent to which the owner’s consent is required for decisions impacting the hotel’s operation. This allows the owner to remain involved in key decisions regarding cash flow. In addition, if stipulated, an owner can place restrictions on expenditure (that is, purchasing systems, concessions or leases). These owner approval rights generally comprise:

- Budget – the operator should submit an annual budget for the owner’s approval, usually 30 to 90 days prior to the start of the fiscal year. Owner approval of the annual budget is usually negotiated, but such approval may depend on the conditions of the performance test, and may therefore exclude certain line items. If both parties do not come to a consensus on a specific line item, an increasing number of agreements have provision for an independent expert to be appointed to adjudicate and provide a determination. In the meantime, the budgeted amount will be calculated using the last year’s approved amount, multiplied by the increase in the Consumer Price Index for that year. The annual budgeting exercise is one of the most collaborative activities between the owner and the operator during the life of a management contract;

- Employment of key senior management positions – the management contract will specify whether the hotel’s employees are employed by the owner or the operator. Generally, each party prefers to pass the responsibility of employment to the other, because of liability issues. For most cases in Europe, the staff are officially employed by the owner. However, generally the operator has the responsibility of hiring and training the line-staff personnel. In a significant proportion of management agreements, owner approval is only required for the hiring of certain key management positions (that is, general manager, financial controller and, sometimes, director of sales and marketing and director of food and beverage). With the owner in most cases being the employer of the hotel’s staff, this enables continuity of employment – and the hotel’s operation – if and when the contract is terminated. Some senior management may be employed by the operator, with the payroll for those staff being charged back to the hotel operation. By and large, all contracts that require the owner’s prior consent for the appointment of senior personnel usually restrict the number of rejections by the owner to two or three candidates presented by the operator each time such a position is to be filled;

- Outsourcing – this clause affects the decisions involving the appointment of an external service provider in relation to the hotel’s operations, such as engineering services or housekeeping. Usually, the terms of such contracts are no longer than 12 months. Owner’s consent is rarely required, unless the contract is significant and above a certain amount (similar to capital expenditure, for which consent is required) or has a duration longer than, say, 12 months;

- Capital expenditure – detailed in the next section;

- Leases and concessions – such clauses relate to the leasing out of hotel space to third parties, such as restaurants, spas, gift shops, beauty salons or retail outlets. Most owners will require restrictions on such agreements, as long-term agreements may complicate a future sale and may not always be the most profitable use of the space with the passing of time, or even in the first place.

5. FF&E and Capital Expenditure

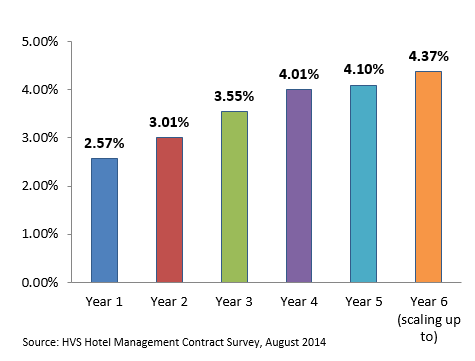

To maintain the asset in a marketable condition and replace the furniture, fixtures and equipment (FF&E) of a hotel at regular intervals, a ‘sinking’ fund is created to raise capital for this periodic FF&E replacement, which is usually a percentage of gross revenue and somewhat dependent on the positioning/level of the hotel. Included in this category are all non-real-estate items that are typically capitalised rather than expensed, which means they are not included in the operating statement, but nevertheless affect an owner’s cash flow. Generally, management agreements include a reserve for replacement of FF&E of between 3% and 5% of gross revenue per month, with the lower percentage more likely to relate to budget hotels and the higher percentage to upper upscale and luxury hotels. This percentage often increases during the first few years of the hotel’s operation, until it reaches a stabilised amount, usually by year five but sometimes not until year ten, as shown in the following table.

Figure 4: FF&E Reserve Contribution

In some cases, the amount to be reserved may be dictated by the lenders financing the hotel. Typically, capital improvements are split into two categories:

- Routine capital improvements: funded through the FF&E reserve account and required to maintain revenue and profit at present levels;

- Discretionary capital improvements (also called ROI capital improvements): investments that are undertaken to generate more revenue and profit, such as the conversion of offices into meeting rooms. These require owner approval and are in addition to the funds expended from the reserve account. Capital expenditures are typically made in lump sums during hotel renovations. In general, soft goods for a typical full-service hotel should be replaced every six-eight years, and case goods should be replaced every 12-13 years.

Within a management contract, the owner is responsible for providing funds to maintain the hotel according to the relevant brand standards. If management chooses to postpone a required repair, they have not eliminated or saved the expenditure, but merely deferred payment until a later date. A hotel that has operated with a below average maintenance budget is likely to have accumulated a considerable amount of deferred maintenance. An insufficient FF&E reserve will eventually negatively impact the property’s standard or grading, and may also lead to a decline in the hotel’s performance and its value.

An integral component of a market area’s supply and demand relationship that has a direct impact on performance is the current and anticipated supply of competitive hotel facilities. By including a territorial restriction (also sometimes referred to as an ‘area of protection’) in a management contract, an owner is assured that no other property with the same brand is allowed to open within a certain radius of the subject hotel, for a certain period of time (ideally being for the whole duration of the agreement) in order to minimize or even pre-empt any form of cannibalisation from the same brand, or sometimes also from another brand of the same company. Depending on the location, the city size and the type of brand, this clause may vary significantly. Upscale/luxury hotels tend to have a territorial restriction area for a larger radius and for a longer period of time than budget/mid-market hotels. Additionally, operators with a larger portfolio of brands may be more agreeable to a larger period of time, or a shrinking restricted area for the exclusion of certain brands, or the exclusion of all brands. Operators will inevitably seek for a more flexible scheme, so that such a constraint does not interfere with the development of the operators’ other brands which are not direct competitors (for example, upscale brands compared to budget brands). Therefore, to define the territorial restriction, the negotiations should be centred around the area of the exclusion clause, the brands that will be included in the clause, the period of time and also the provision of an independent impact study of the development of a similar brand on the subject property’s performance. With the recent consolidation of the hotel industry (the Marriott/Starwood merger, the purchase of FRHI by Accor Hotels) negotiations are more and more focused on the risk of chain acquisition carve outs, the prospect for any hotel that is a member of a chain of hotels where it is intended that one or more of the hotels of the chain will be rebranded to the same brand as the subject hotel.

Hotel management contracts often include a non-disturbance agreement. This is an agreement between the hotel operator, the owner and the owner’s lender. In the event of default or the owner’s insolvency, the lender takes over the ownership of the hotel, agrees not to terminate the existing management contract and remove the manager after a foreclosure. At the same time, the hotel operator agrees to stay and operate the hotel for the lender in case of insolvency or enforcement. The hotel operator can be confident in keeping the value of the management contract, and in having a direct contractual relationship with the lender. On the other hand, the lender knows the operator can’t leave the contract immediately on insolvency or a default, which is potentially disruptive to the business.

8. Operator Guarantees

An operator guarantee ensures that the owner will receive a certain level of profit or net operating income. If this level of profit is not achieved by the operator, the operator guarantees to make up the difference to the owner through their own funds. For example, if the contract states a guarantee of €1,000,000 per annum, and the operator only achieves €800,000, the operator will then make up the remaining €200,000 from their own resources. Operator guarantees are not to be confused with an owner’s priority return, which reflects the hurdle of a particular performance (such as GOP) before receiving the incentive fee. For example, if the owner’s priority return is equal to €1,000,000 and the GOP achieved in a particular year is €800,000, then the operator will not receive an incentive fee. If the GOP in a particular year is €1,200,000, then the incentive fee will be payable. It is typical when such guarantees exist that there is a provision for the operator to ‘claw back’ any payments made under a guarantee out of future surplus profits. Equally typical is the tendency for the operator to place a limit (‘cap’) on the total guaranteed funds within a specified number of years. When the operator fails to receive an incentive fee, this is sometimes referred to as a ‘stand aside’. Some contracts allow for this to be paid once future profits are earned to cover the shortfall. The current trend is for a shift away from operator guarantees. Over the last 15 years, operators have been placing limits on guarantees to exclude force majeure factors in order to cover their future liability. As such, operators will generally require higher fees in return for an operator guarantee and this may not always be cost-effective for the owner. In addition, most contracts will include a cap on the level of operator guarantee, as noted above.

9. Operator Key Money

A more prevalent way to incentivise owners and secure contracts is when operators use their balance sheet to offer either key money or sliver equity. Key money, in the context of management contracts, can be defined as a financial contribution from the operator to the owner’s investment cost related to the development of the hotel. Often regarded as an evidence of the operator’s genuine interest in the engagement, key money can be a valuable resource to help a brand expand into new markets without the high development costs and to seal the deal for trophy assets. Many operators offer the key money as a ‘loan’ to the owner, which could be either towards the hotel’s development or its preopening, or to cover part or all of a renovation in the case of the re-branding of an existing hotel. However, key money comes at the expense of something else, usually higher fees and/or a longer term. Moreover, almost all operators require the owner to repay a prorated amount of the outstanding key money, with or without interest, if the contract is terminated prior to the end of the term or an agreed part thereof. For existing properties, key money may be offered at the time of signing or after the capital improvements (recommended by the operator) have been completed. Conversely, for new hotels, key money is mostly offered as the last funding available to the owner, paid on the opening of the hotel. According the the HVS Hotel Management Contract Survey, a large majority of the European contracts that offer key money are for upscale/upper upscale/luxury hotels. However, key money does not entitle the operator to an actual equity share in the investment. In today’s highly competitive market, some operators now assume an actual ownership position in the hotel. An increasingly common tool is minority equity stake where the operator makes a financial contribution in return of a stake (from less than 5% to 30%) in the ownership of the hotel. Under such an arrangement, if the hotel performs well the operator directly realises a return for the investment. Equity contributions by management companies may help to align the interests of the owner with the management company. The benefit of reducing an owner’s need to use their own cash is a powerful incentive. However, owners should also be aware of the potential risks or trade-offs associated with forming equity partnerships with management companies. More partners imply more parties to split the profits, and less owner equity means a higher chance of losing control of the property. In addition, the relationship with the management company as an equity contributor may limit the owner’s ability to terminate the management agreement[2].

10. Termination Rights

Each party may choose to terminate the hotel management agreement for a variety of reasons: bankruptcy, fraud, condemnation, unmet performance standards, sale. As hotels are becoming more mainstream assets, owners are getting more mature and vigilant on the conditions for termination and the associated operator fees. Owners can negotiate the right to terminate the contract upon the sale of the hotel to a third party. This clause gives flexibility to the owner or to any potential investor as it allows the owner to realise the investment and sell the hotel unencumbered. The operator is compensated with a termination fee from the owner. The termination fee is usually an amount equal to the average management fees earned by the operator in the preceding two-three years (24 to 36 months) prior to the date of termination, ‘multiplied by’ either (i) the remainder of the term (years/months) or (ii) a multiple of two, three, five or any other as agreed upon. With a more upscale brand, the operator will be more sensitive to not being ‘kicked out’ because they have substantially invested in sales and marketing to create an upscale brand. Operators will also argue that an early termination could be damaging to their brand. Termination without cause allows the owner to terminate the contract without any justification. The termination fee under this provision is normally calculated in a similar method as for the termination upon sale. Termination without cause, or on sale, is more common in contracts with independent operators. The operator performance test mentioned earlier allows the owner to terminate the contract if the operator fails to meet the performance expectations and does not use its cure rights. The testing periods for most performance termination clauses begin three years after the opening of the hotel or the inception of the contract to allow the hotel to reach stabilised operating levels, and the performance failure usually has to persist for two consecutive years.

Other causes for termination consist of operator misconduct, condemnation, bankruptcy and default. We should stress here that management contracts without termination on sale provisions obviously reduce flexibility on exit. It is usually worse when the operator has an equity stake in the property. An owner should always look for the most flexible management contract terms that can be negotiated.

Current and Future Trends

While owners have become far more knowledgeable in recent years, major global operators have also become larger and more powerful, particularly given the recent consolidation and mergers and acquisition of hotel operators in the industry, and therefore the reduction in competition has made it more difficult to negotiate with them. It is also reasonable to state that there is a move towards agreements with third-party operators. As the hotel is becoming a more mainstream asset and owners are gaining a better understanding and maturity, third-party operators (TPO) are on the rise. Well established in the US market, this model, relatively new in Europe, is now growing rapidly, bringing more flexibility to owners and allowing them in some instances to defer the responsibility of the staff to the TPO’s balance sheets. A hotel managed by a TPO is very often combined with a franchise for a major hotel brand. Another trend is the emergence of ‘manchises’ and hybrid management contracts, whereby hotel owners engage a hotel operating company for an initial period of time, say three to five years, after which the contract transfers to a franchise contract in which the owner assumes management responsibility and retains the operator’s brand, in exchange of an annual franchise fee payment. To the outside world, there is no apparent change. This is particularly advantageous to help hotel operating companies launch new brands, enabling strict operating controls to be established in the initial years as the brand is going through its ‘ramping up’ period.

Conclusion

Hotel Management contract negotiation can be a long and complex process. This negotiation should satisfy both the operator and the owner to help ensure an effective and trustful relationship between the two parties, while taking into consideration the asset value. On one hand, the operator will require stability in cash flow with a longer-term contract. On the other hand, the owner will primarily look for flexibility from an exit perspective, visibility on the profit and loss of the asset and transparency on the fee structure, and from that goal, the owner may use a third-party operator, which could be more aligned with their interests. The main goal when negotiating is to avoid uncertainty and conflict, and look for clarity and trust in order to maximise each parties’returns. This is critical to ensuring that responsibilities and best practices are met and the business is run successfully.

Note: Please note that the terms mentioned in this article only cover some of the major characteristics of the contract. Today’s management agreements are defined by a variety of formats and level of detail. Some contracts are becoming much more complex and comprise new terms not discussed in this article. It is therefore important to review the contract terms in detail. Each party should be assisted by an external independent legal advisor in order to deal with these complex legal documents.

[1] From a sample of 76 management contracts in Europe with results compiled in the following article: Thadani, Manav, mrics & Mobar, Juie. ‘HVS Hotel Management Contract Survey’. HVS India. August 2014. [2] Isenstadt, Todd & Detlefsen, Hans. ‘Hotel Management Companies and Equity Contributions: Benefits And Risks’. HVS Chicago. August 2014.