By Allison Fogarty

Considering a trip to an island I haven’t been to recently, and being somewhat flexible in timing, I was startled to realize that, given a reasonable lead time, it would be 25% cheaper to fly to London than to my island destination.

Once again, we come up against the hard reality of Caribbean destinations – flying to Paradise is more expensive, and offers far fewer scheduling options, than flying to other destinations. What is the implication of this for the region?

The most important source market for most Caribbean tourism destinations is the United States, although several islands are more dependent upon historic trading partners: UK tourists outnumber US residents in Barbados, the Netherlands dominates Curacao tourism, while French visitors predominate in Martinique and Guadeloupe. Markets have also shifted over time: the Dominican Republic, once dominated by European package holiday tourists, has gradually become more dependent upon US visitors, although all-inclusive hotels continue to dominate the lodging market.

Hotels in the Caribbean have always had to overcome numerous challenges to profitability: High wage costs, frequently inflexible government labor policies, import tariffs, freight charges for supplies and stores, and shortages of skilled managers and employees all squeeze the bottom line. But one of the most fundamental difficulties of all has always been the ability to transport guests to Caribbean destinations on a convenient schedule and at a reasonable price. According to hoteliers, even the wealthy won’t pay more to fly to the islands than they will to fly across the US or to Europe, and the privileged aren’t used to being inconvenienced. And, since affluent consumers have the world to choose from, they can simply choose another destination.

Airline capacity or “lift” has always been a challenge in the Caribbean. Tourists and residents alike are dependent on air transportation move around the region, and thus compete for affordable airline seats. Many island nations have diaspora working or living in other countries that return home periodically to visit, while residents may take occasional or frequent trips abroad for business or vacation. Notably, Caribbean residents have a far higher rate of international air travel per capita than the world average. These native-born travelers compete with tourists for airline seat capacity, and because locals are apt to plan trips well in advance, islanders can frequently secure the less expensive excursion fares, leaving the higher fare categories for the tourists, particularly those that seek impromptu escapes to sun and sand.

Air fares are also affected by the taxes and fees that many governments, including the US, impose on the price of air tickets. These taxes and fees vary greatly from country to country: $121 per roundtrip ticket in Jamaica, $82 to the Dominican Republic, $105 to the Bahamas, $75 to Antigua, $41 to San Juan, and $56 to St Thomas, to cite a few examples. For Americans, US Taxes add another $63 to international fares. So, if a base advance purchase airline fare of $250 from the US is available, the total ticket price could range from $281 for a Puerto Rican getaway to $434 for an excursion to Jamaica. Governments may consider the taxes they can collect from travelers, rather than voters. They may be less likely to think about the impact of fees on airfares or the potential tourists that may be deterred or diverted to the ubiquitous cruise ships by high airfares.

All too frequently the profits of Caribbean hotels have ebbed and flowed along with airline service to the region from major source markets. Whenever a carrier pulls out, merges, or goes broke, a period of turmoil follows, as remaining carriers to affected destinations can and do increase their fares, and local authorities scramble to attract alternate carriers. Several countries including The Bahamas, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, the Cayman Islands, and Antigua and Barbuda have invested in national flag carriers to ensure consistent service; however these regionally-based carriers have frequently had difficulty maintaining consistently profitable operations. Locally based carriers also tend to be less popular with US travelers, many of whom seek to either earn or use frequent traveler points.

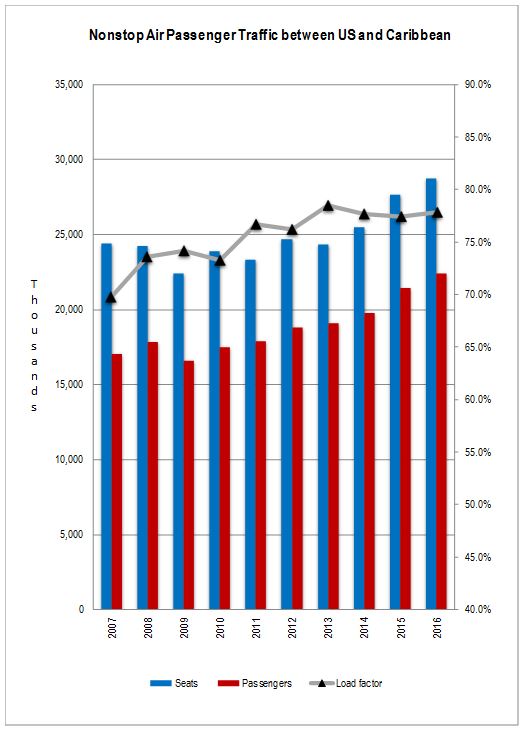

As the cost of Aviation fuel increased sharply in 2008, US airlines scrapped older, less fuel-efficient equipment that were employed on marginal routes. Shortly after the oil price spike, the mortgage market collapsed, and everyone adjusted to reality of recession. Airline seat capacity between the US and the Caribbean region was reduced by 8%. Unsurprisingly, demand also declined, and passenger traffic between the Caribbean and its largest tourist market declined by almost 7% between 2008 and 2009. The good news is that since that sharp decline in 2008, both seat capacity and demand have increased; the number of seats on non-stop routes between the US and the Caribbean is up by over 18 percent from the pre-recession peak in 2008. Traffic has increased ever more rapidly however, and for the 12 months ended June 2016, passenger traffic was up by over 25% from the12 months ended June 2008, implying a growth rate of 2.9% per year. Since 2013, overall nonstop passenger traffic has increased by 17% on US to Caribbean routes, while traffic on US carriers increased by 21%; the number of seats climbed more slowly. Nonstop US-Caribbean capacity increased by 18% overall and by 15% on US carriers. As of June 2016, passenger traffic between the US and Caribbean grew by 4.5% outpacing the growth in seats of 4.0%. traffic on Us carriers increased by 5.3%, while the number of sets grew by 4.0%.

So, as many of us have noticed, those flights are getting more crowded! Airlines, like hotels, measure occupancy. Back in 2008, annual airline load factor (seat occupancy) on flights between the US and Caribbean was 74% – considered excellent at the time, since loads had increased sharply from the high 60s. However, over the past 10 years- through mid-2016, overall load factor on flights between the US and the Caribbean increased to 78% – and on US carriers it’s even more crowded. Most hoteliers would envy the occupancy increase on scheduled flights by US Carriers, which has has increased by 10 points -from 74%, (same as the overall) to 80% in June 2016. Foreign carriers operate at a more marginal load factor of 67%. According to the US DOT, the overall international load factor for US Airlines is approximately 80%, so generally, Caribbean routes are performing well.

The largest routes – those with the most capacity from the US are the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and The Bahamas, which together represent 57% of regional capacity, and 53% of the passengers carried. Consequently, the load factor to these destinations is low by regional standards – only 73%. Closer examination of the statistics indicates that passenger loads on Jamaica-bound planes are comparable to the overall average, while passengers on planes bound to the Dominican Republic and Bahamas are most likely to have room to spread out, since load factors average about 70%. However, planes bound from the US to other Caribbean destinations are getting ever more crowded – seat occupancy has climbed to over 84%, well above the international average in 2016, from 79% in 2013. This may be a sign of increased capacity to come, as traffic certainly seems to support the development of additional capacity, particularly to some of the less-trafficked destinations.