By Erich Baum

Portland, Maine, is the northernmost outpost of the Atlantic Seaboard, host to a six-month winter and minor league hockey. A small, third-tier city, with steady but slow economic growth, Portland’s downtown hotel inventory recently grew from five to ten properties over a six-year period. Why did developers and loan underwriters think there was enough demand potential to support approximately 1,000 new rooms, a 127% increase? Because it could, evidently. Credit goes to induced demand.

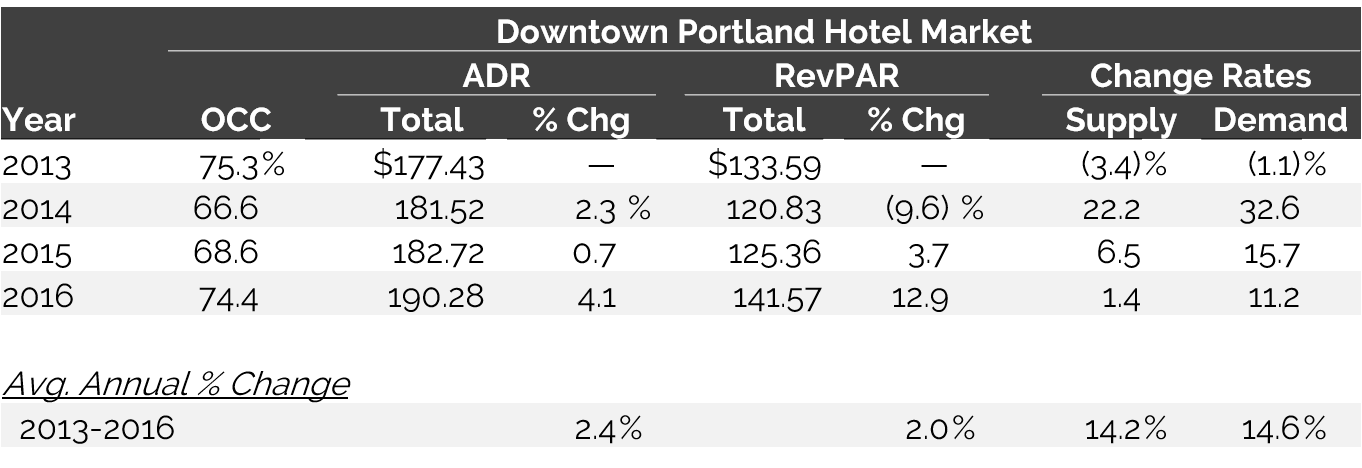

Downtown Portland Lodging Market Trends The following table details key rooms-revenue metrics for Downtown Portland between 2013 and 2016.

Downtown Portland Lodging Market Trends – Key Rooms-Revenue Metrics

As of 2007, Downtown Portland contained four good-quality hotels with roughly 550 rooms. A fifth hotel of approximately 200 rooms operated on the margins in a state of disrepair. Occupancy and average rate (ADR) levels were healthy and stable, but short of eye-popping. Then, beginning in 2009, affiliates of Residence Inn by Marriott, Hampton by Hilton, Courtyard by Marriott, Hyatt Place, and Marriott’s Autograph Collection opened successively, and the derelict hotel noted above was closed, rehabilitated, and expanded into a 289-room Westin. Supply grew at an average annual rate of 9.1% between 2009 and 2016, with most of the growth realized in 2014 and 2015 (as noted above). The rapid expansion might have turned out as another example of the hotel industry getting ahead of itself; another instance of aggressive development and profligate lending. But something else happened instead. By 2016, the results were in, and they were unequivocally positive. In that year, the first full calendar year of operation after the last of the new hotel openings, Downtown Portland reached new ADR heights and near-peak occupancy levels.

A Working Waterfront and Cobblestone Streets Downtown Portland is peninsular, with three coasts. The Downtown district is surprisingly hilly; plows and salt keep it navigable in winter. The centerpiece is the Old Port, a multi-block historic district of cobblestone streets and an exploding restaurant scene. The architecture and streetscapes provide a distinctive sense of place, and the waterfront, with its rickety wharfs and piers, remains a working port. Despite the many charms of the Downtown core, Greater Portland can also be relegated to third-tier-city status: one characterized by a stable, slow economic growth rate. The Downtown district contains a small and static inventory of office space. Most of the region’s major employers are based in the suburbs or nearby towns with their own character, like Freeport, home of L.L. Bean. With no convention center, the city’s only large-scale gathering space is a civic center that opened in 1970s. ZZ Top was the first headliner. The arena is best known as the home of minor league hockey’s Portland Pirates.

Often, when the opening of new hotel inventory coincides with material demand growth, the group segment does the heavy lifting. New hotels with significant meeting space have a means of self-generating occupancy. Among the new hotels in Downtown Portland, however, only the Westin has a significant allotment of meeting space. Construction of the other hotels was based on faith in surplus transient demand, suggested mainly by the strong performance of the existing Hilton Garden Inn affiliate, the lone downtown hotel with an esteemed brand. The Old Port’s emergence as a dining destination served as a positive indicator, as well. But against the burden of filling roughly 1,000 new rooms, the evidence looks scant.

And yet the new, almost 350,000 room nights of annual capacity were filled at a rate of 77% in 2016, stronger than the pre-recession occupancy rate. Pricing also surged. The new hotels thrived by accommodating excess demand (previously turned away due to lack of capacity) and by stimulating new demand through the advertising and promotional efforts of the hotel staff and their brands’ marketing and frequent-guest programs. In the case of the new Marriott Autograph Collection and Westin affiliates, the quality and scope of the facilities also played a role in reaching new markets. Combined, these dynamics encompass the phenomenon of supply-induced demand.

Supply-Induced Demand, Clarified For the most part, when demand is “induced” by new supply, occupancy that was historically accommodated elsewhere is captured by the expanded market in question. Before the rapid expansion of Downtown Portland’s hotel inventory, leisure travelers who were a) unable to stay in Downtown Portland because of insufficient capacity but, b) sought a Portland-like experience, had numerous comparable options. They chose Freeport, Maine; or Portsmouth, New Hampshire; or Providence, Rhode Island; or Boston, Massachusetts. And where travelers with business to transact in Portland were concerned, those who now stay Downtown mostly stayed in South Portland, in one of the many hotels near the Maine Mall. Induced demand is largely demand that is re-routed to a location/product that is either more preferred, or was preferred in the first place but unavailable.

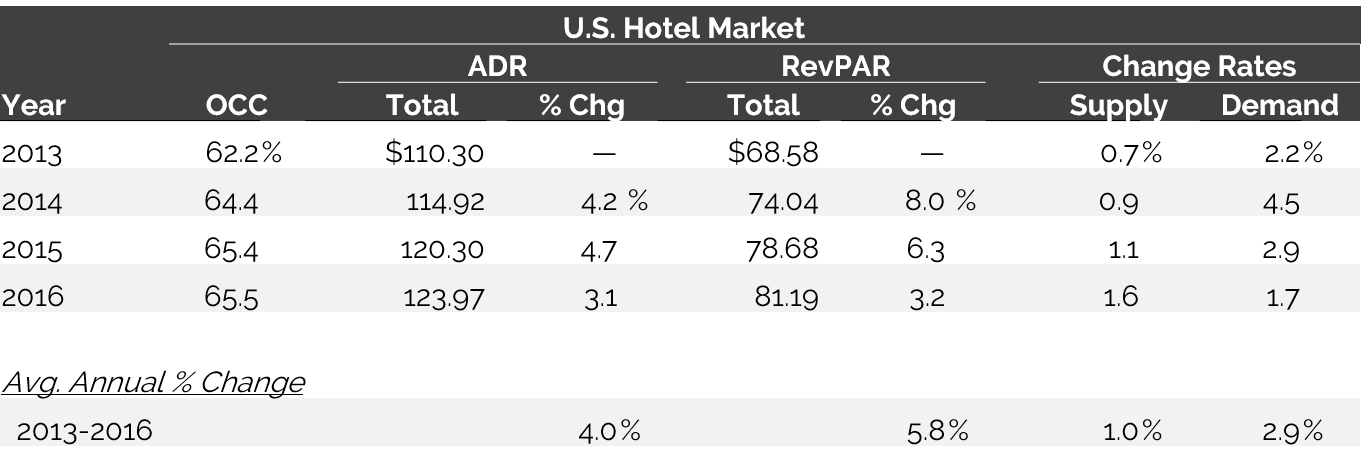

Hotel demand in the broadest sense is born in economic activity, which creates both the need for travel (for commercial purposes) and the disposable income necessary to support the human want for travel (for leisure purposes). In this broad context, hotel demand grows proportionate to economic growth. Looking at the lodging industry on a national basis is instructive in this regard. The following table summarizes key rooms-revenue metrics for the U.S. lodging industry between 2013 and 2016.

U.S. Lodging Market Trends – Key Rooms-Revenue Metrics

Comparing the national supply and demand change rates with those of Downtown Portland, far less volatility is in evidence, which is reasonable considering the national survey encompassed approximately 4.5 million hotel rooms, compared to roughly 750 rooms in Downtown Portland. A larger sample smooths out the bumps of volatility. The national statistics, because of their scale, also serve as the best measure of base economic change. Between 2013 and 2016, the national lodging market’s demand grew at an average annual rate of 2.9%, basically in line with underlying national economic growth over that period.

By comparison, Downtown Portland’s demand grew at an average annual rate of 14.6% over the same period. Seen as a microscopically small share of the national lodging market, Downtown Portland’s above-national-market rate of gain is balanced by below-national-market results in some other market or markets. Supply-induced demand is largely a measure of one or several new hotels’ ability to consume some other hotel market’s lunch.

Predicting Success Supply-induced demand is common. For any market that experiences at least one sellout night per year, a new hotel—even a charmless rooms-only hotel—will technically induce demand when it accommodates a single stay that was previously turned away. Predicting how much demand can be induced is the challenge. Meeting space helps, but new-build full-service hotels in anything but the most urban of locations are increasingly rare. Otherwise, prospects are generally tied to questions of high-season market depth; the likely emergence of new demand generators in the market; or the exceptional features, facilities, or branding of the new hotel(s) in question.

Analysts can also cite comparable market data, such as the experience in Downtown Portland, which, in hindsight, was ripe for expansion. Growing wealth in travel-hungry feeder markets throughout the Northeast, and these travelers’ preference for coastal urban settings with a vibrant dining and nightlife scene, have proven to be major catalysts. The city is renewed and ascendant, and is being appreciated by new generations for its indelible charms and authenticity. Investors in Portland’s new hotels have largely been rewarded for their vision and confidence in the market’s potential, and doubters have been edified.